West Africa: Ghana, Togo, Benin Trip Report

Reported by Brooke Berlin

Text and photographs are provided through the courtesy of Johann Van Zyl and Brooke Berlin.

Voodoo, Drumming, and Death

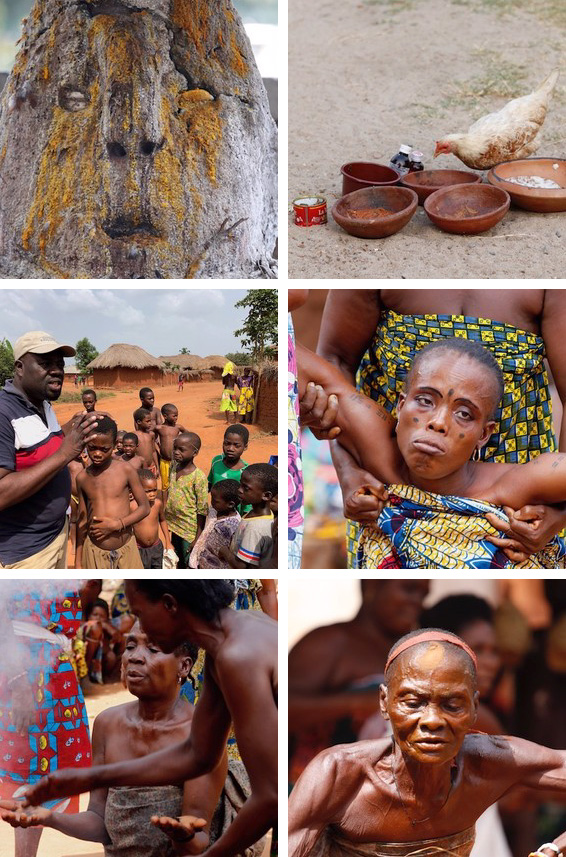

We start slowly in Lomé with a visit to the Fetish Market, to learn about the assorted ingredients necessary for potions, concoctions, amulets, and offerings. Going into it we thought it would be a kitschy tourist attraction, with an attitude of “if you’ve seen dusty skulls and skins you’ve seen a fetish market” but we were wrong. In the middle of the merchants was a shrine that had recently been used for a festival offering and we could still make out the seared feathers and thick blood. Voodoo in West Africa encompass a much wider healing and spiritual practice than the stereotypes (like needles in a doll to hurt your enemies) we've been exposed to in film and TV. While we were walking around a local man arrived on his moto to buy a bagful of items (people who proudly practice voodoo will come during the day; government, church, and society members prefer private nighttime shopping when spying eyes can’t see them). Sadly, we saw the reality of the poaching we work to prevent in other parts of Africa, with at least five fully-grown pangolins available for purchase alongside other animals, which broke my heart. This is the reality of visiting voodoo communities and some people may have a hard time with it. We met with a medicine man who blessed an amulet for safe passage so that our travels would be protected and positive.

During the drives, we see various shrines next to trees, in front of homes, at cross-roads in the center of towns. We learn about the reoccurring significance of palm oil, water, fire, and alcohol in ceremonies and the divinities who manifest for each: Sakpata (god/dess of earth), Mami Water (god/dess of the sea), Heviesso (god/dess of fire), etc. Each of the various tribes does their traditional ceremony on a different day or at a different time of year; nothing is a guarantee. During our December visit, we feel that Benin is the bee’s knees of voodoo, but at another time of year Togo could be just as transcendental.

En route from Lomé to Grand Popo we turn off the main Trans-African Highway, a paved two-lane highway from Dakar to Lagos, to participate in our first of many ceremonies. There is no way we would have found, or ventured into this, alone. Noah knows where to direct us, makes instant friends with the children who come to greet us, and ensures we are familiar with formalities, like greeting and thanking all of the elders in a specific order, sitting where we’re supposed to, participating when appropriate (as he does with every ceremony we attend). The frenetic rhythm of the drums and the chilling chants of the initiated call the spirits who then possess the dancers who fall into trance: eyes rolling back, grimaces, convulsions, insensitivity to fire. Though very real and authentic, we never felt afraid or uncomfortable.

There are countless unique and meaningful masks in West Africa and we attend various ceremonies that honor different ones. A boatride up the Mono River, which creates the border between Togo and Benin, brings us to a village where the Peda tribe is getting ready for their Zangbeto Mask Ceremony. The Zangbeto, which Johann henceforth refers to as a “roomba”, is a tall, cylindrical, straw-covered creation that represents a spiritual police force. It comes out from the temple and spins, spins, spins … a spiritual cleaning of the village as it protects against bad spirits and malicious people. The Zangbeto performs “miracles” to prove its powers, and the one that made me a believer was when it “levitated” and a small, live crocodile ran out from under it and right toward me. A townsman caught it and brought it over so we could touch it, which I declined to do at the same moment as it started to pee on me; this is definitely a different sort of cleansing than I’m used to at home in Boulder, Colorado!

In Ketou we attend a Gelede Mask Ceremony. This is a traditional ceremony of the Yoruba ethnic group. Dedicated to Mother Earth, the head priestess of Gelede is a woman, however only men wear the masks and perform the dance. They are commemorating when they were accepted back into the community after mistreating the women and being forced out, and use the masks to educate the population about positive actions: from the traditional theme of honoring women to modern themes of sleeping under mosquito nets to avoid malaria, using condoms for safe sex, going to school for education, using an ATM to save money, etc. It is a fascinating mix of street performance and magical theater. UNESCO listed Gelede as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. I find it ironic that the one performance based in honoring and respecting women is the one where a live iguana is tossed in my direction as part of a practical joke, making for one of the more heart-stopping moments of the trip.

Another Yoruba ceremony is that of the Egungun Masks, which represent the spirits of the deceased. We attend this dance in Dassa, and are enthralled with the performance. The costumes are of heavy, multi-layered, multi-colored cotton that move effortlessly as they move around the village square chasing spectators. Each Egun has a handler who helps to keep the Egun from touching anyone because the belief is that someone touched by the Egun could “die” temporarily, and we do see one man fall stiff as a board to the ground and then be carried off to a nearby temple to be revived after exactly that happens. See Video below (especially from around 1:30 into it).

Between the heat, a possible intake of gluten, and a bit of “what’s-the-next-animal” anxiety, I’m not feeling well, and when I lose my lunch in the middle of the festival, the village participants think I’ve also been touched by an Egun and am going through a rebirth of my own.

One of the most real and raw moments was when we visited the Dankoli Fetish, a shrine used by ancient animistic cults. This one is located on the roadside, and we get out of the car to approach the shine and learn about the process: hammer a wooden peg into the ground surrounding the fetish, pour palm oil and spray palm alcohol onto the area, repeat your wish, which can be anything from a happy marriage and an easy pregnancy to professional success and abundant harvests, and finally stating what your sacrifice will be dependent on the magnitude of your request. While Noah is telling us this, a man appears on a motorbike with a goat tied up. “We are lucky”, Noah tells us, “this man has brought a goat he promised to the fetish, as his wish came true, and now they will sacrifice the goat.” Which they did, as swiftly as ever! A knife was sharpened, the neck cut, blood dripped all over the shrine, and all the while a fire was started to cook the meat, which takes place as Johann and I are instructed to pound our own wooden steak into the shrine. After only a few weeks at home and the beginning of 2019, it seems this fetish works and I now have to send my own promised offering.

In Togo we visit the Bassar tribe to see the Fire Dance. The Bassar are also well-known for their primitive iron making and for their Harvest Festival in September as they are considered to grow the best yams in all of Togo and Benin. I like this village very much as it is the first we come across where people can speak English, and I spend time talking with two sisters and their brother who are all in school, and while it is about an hour away, they will be starting secondary school soon. I find out that the king of this village is well educated and supports the education of the people of his village, which includes these young women. As the Fire Dance is taking place – with men dressed in their dance party skins and elaborate iron leg wraps that highlight the rhythms of the drums as they get down to the music and get on top of a pile of hot coals – I sit with the king and talk about mutual interests, such as beaded African necklaces.

Kumasi is the historical and spiritual capital of the Ashanti Kingdom. The Ashanti were one of the most powerful Kingdoms in Africa until the end of the nineteenth century, when the British subsumed Ashanti Country into their Gold Coast Colony. Today, Kumasi, with a population of nearly one million, is home to one of the largest markets in Africa and still a central trading center. We visit the Ashanti Cultural Centre to learn about the rich history of the Asantehenes (Kings); are able to join in a traditional Ashanti funeral, which is really a joyous celebration of the person’s life; and tour the impressive Royal Palace Museum. The pièce de résistance of our cultural ceremonies however, was being in Kumasi for the Akwasidae Festival. This pageantry of riches is a very special celebration for the Ashanti and takes place every 42 days. Taking place at the Royal Palace, there is a procession of all the royals and officials of the Ashanti kingdom, leading up to the King himself.

The King is carried out in a palanquin, adorned in vivid Kente designed and produced for him for each separate occasion along with massive amounts of centuries old gold jewelry, and is positioned under a spectacularly elaborate umbrella, surrounded by Ashanti elders and advisors, with a narrow but dense passage of dignitaries in front of him. One by one, each individual royal court of the kingdom approaches the King, bringing gifts, reciting stories of the Ashanti history, performing drumming and dance, shooting guns into the air, and more. We were welcome to walk around and enjoy the festivities, which went on for about five hours.

UNESCO and The Story of the Slave Trade:

We spend a morning on Lake Nokwe, Benin, admiring the bustle of a fishing-centric lifestyle and boating out to Ganvié (a UNESCO World Heritage site). Ganvié, meaning “place where people found peace” is the largest and most beautiful African village on stilts. The 25,000 inhabitants of the Tofinou ethnic group, meaning “the people who love water”, escaped capture into the slave trade by moving onto the water and building wooden homes on teak stilts. Dugout canoes bring children to school, women to market, and men to fish. We stop at a popular hotel/market, run by a Marina, a sharp business woman who owns the hotel, which she inherited from her mother. We admire each other’s fashion and eventually negotiate a fair price for a dusty Yoruba beaded headdress found in a far back corner of her shop. It's now on our mantlepiece in Boulder!

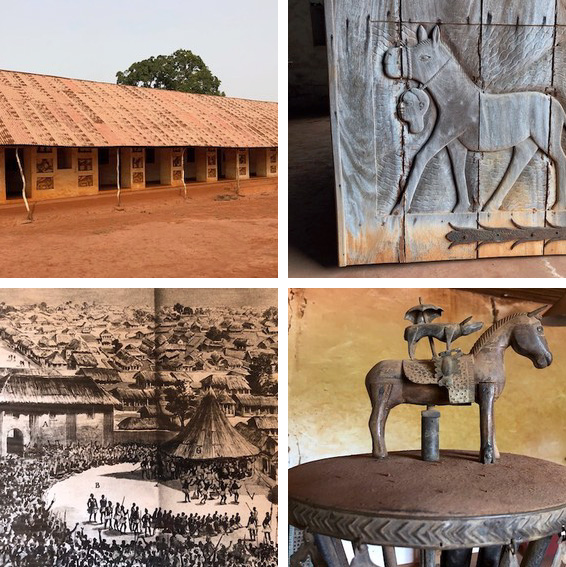

Benin used to be called Dahomey. In 1975, the name was officially changed to Benin, which in the Yoruba language means “we are here, we are fine”. This Yoruba word was chosen because the Yoruba aren’t from the area that comprises the country, and so none of the local tribes could become upset. During the reign of the Kingdom of Dahomey, before French rule, there were 12 kings and their respective palaces (some argue there were 13). The Royal Palaces of Abomey, (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), were once the heart of the Fon people’s most important empire in Western Africa, as great wealth and power were acquired as the Fon sold prisoners of tribal warfare into the slave trade. The two best maintained palaces, those of King Ghézo (father, represented as buffalo) and King Glélé (son, represented as lion), showcase beautiful bas-relief walls, as well as royal artifacts: thrones and umbrellas, altars and statues, costumes and weapons.

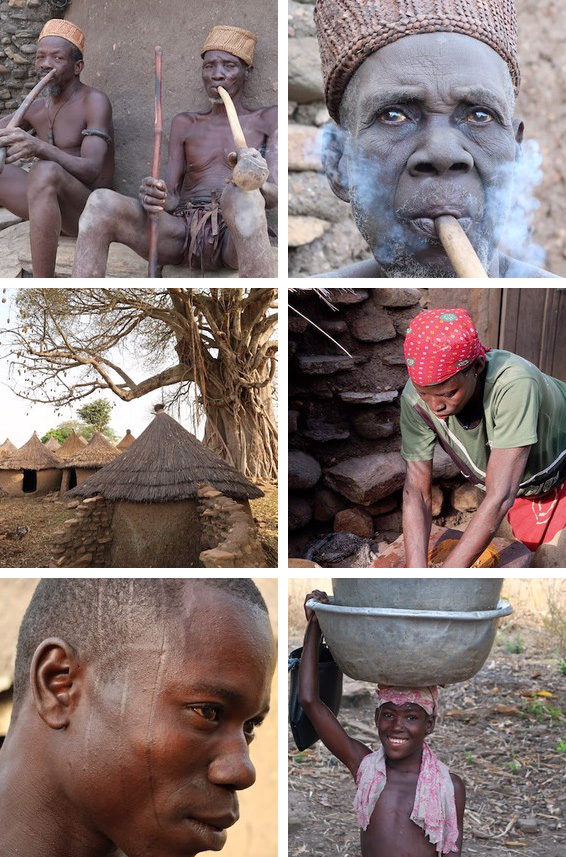

Many people fled their homelands to escape being captured and sold into the slave trade by both the Dahomey of “Benin” and the Ashanti of “Ghana” (in quotes as these regions weren’t known by these modern day names at the time). The Taneka people are a bi-product of this as various tribes from Niger, Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Togo sought refuge in the high, rocky terrain of this mountainous region, and peacefully intermarried, creating a new ethnic group. We walk around the craggy landscape, and visit with a few of the elderly fetish priests who still follow tradition with what they wear (only a goat skin), carry (a long pipe and magical amulets), and do (initiations rites for young men of the community).

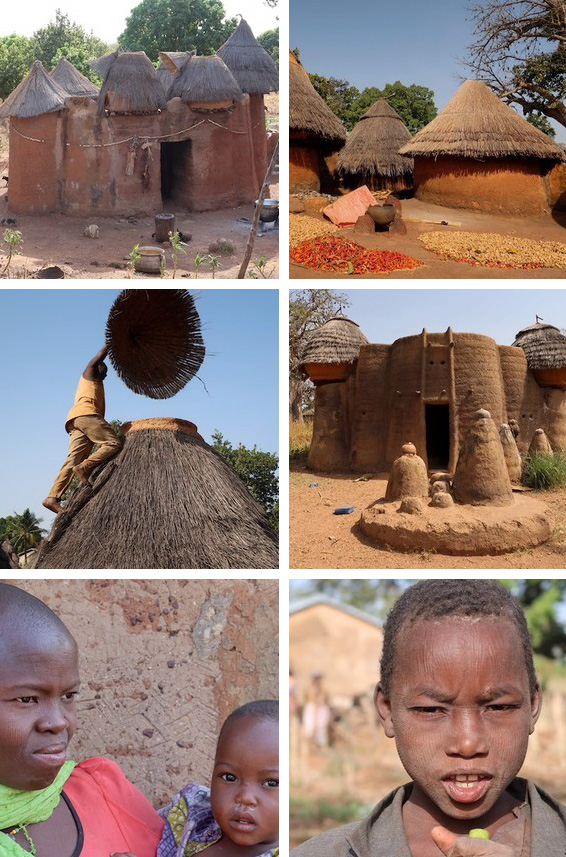

Another ethnic group who lived in such a way as to avoid being captured and sold as slaves, this time escaping Muslim slave traders from the North, are the Betamaribe of Benin and Tamberma of Togo (same people; different location). We meet both, and while the official UNESCO World Heritage Site is an adobe fortified dwelling representing their unique architecture on the Togolese side, we found it to be a more touristy experience and somewhat underwhelming; we much more preferred the experience Noah set up for us by making random stops when he saw a perfect representation of one of these small medieval castle-like compounds. Le Corbusier is known to have described them as “sculptural architecture”. The layers of clay and mud constructed around wood supports make for a soft design with strong structure. Animistic beliefs are honored by large phallic shrines at the entrance and the home reflects their cosmology with the dark ground floor representing death and ancestors and the open-air second floor representing life.

Johann was fascinated running into a hunter equipped with the most ancient gun imaginable. Held together with wire and not much else, it still functions with loose gunpowder and random lead shot.

In Ouidah, Benin, the spiritual capital of Voodoo and also one of the main slave ports of the past. We start at the Python Temple, directly opposite the Catholic Cathedral. I go into the courtyard to see on the main shrines toward the back; Johann ventures further into the actual Python Temple, a barefoot experience among 100 pythons, resulting in one rested upon his shoulders. We then visit the Portuguese Fort for our first touch of the transatlantic slave history of West Africa. Unfortunately, most of the items are replicas with the originals being housed in European museums, however there is a photographic exhibition that showcases the similarities between the voodoo in Benin and Brazil which is really impressive. And finally we walk the slave road from the main auction house to the Door of No Return (a UNESCO World Heritage site), a truly moving experience especially when standing in front of the Memorial of Remembrance, a monument to honor those put into the mass grave on which it sits.